Opmmur

Time Travel Professor

- Messages

- 5,049

400,000-year-old human DNA adds new tangle to our origin story

Alan Boyle, Science Editor NBC News

Dec. 4, 2013 at 1:02 PM ET

Javier Trueba / Madrid Scientific Films

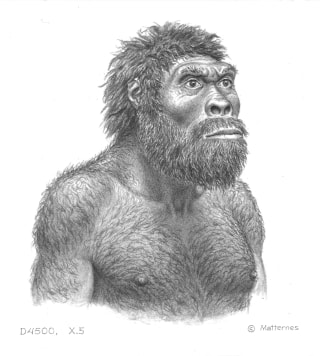

The Sima de los Huesos people lived about 400,000 years ago in Spain.

The oldest human DNA ever recovered is throwing scientists for a loop: The 400,000-year-old genetic material comes from bones that have been linked to Neanderthals in Spain — but its signature is most similar to that of a different ancient human population from Siberia, known as the Denisovans.

The researchers who did the analysis said their findings show an "unexpected link" between two of our extinct cousin species. Follow-up studies could crack the mystery — not only for the early humans who lived in the cave complex known as Sima de los Huesos (Spanish for "Pit of Bones"), but for other mysterious populations in the Pleistocene epoch.

"Ancient DNA sequencing techniques have become sensitive enough to warrant further investigation of DNA survival at sites where Middle Pleistocene hominins are found," the research team, led by Matthias Meyer and Svante Pääbo of Germany's Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, wrote in Thursday's issue of the journal Nature. ("Hominin" is the currently accepted term for humans and our close evolutionary cousins.)

As anthropologists are getting better at extracting DNA from ancient bones, genetic mysteries are cropping up more frequently: Last month, researchers at scientific meetings talked about not-yet-published findings that hinted at interbreeding among Neanderthals, Denisovans and previously unknown populations of early humans.

A new standardThe age of the mitochondrial DNA analyzed for the Nature study sets a new standard: Researchers used statistical analysis of the DNA and other samples to estimate that the material was roughly 400,000 years old. That meshed with the estimated age for similar DNA extracted from bear bones found in the same cave.

More than 6,000 human fossils, representing about 28 individuals, have been recovered from the Sima de los Huesos site, a hard-to-get-to cave chamber that lies about 100 feet (30 meters) below the surface in northern Spain. The fossils are unusually well-preserved, thanks in part to the undisturbed cave's constant cool temperature and high humidity.

Javier Trueba / Madrid Scientific Films

The thigh bone of a 400,000-year-old hominin yielded mitochondrial DNA for analysis.

Researchers drilled a series of tiny holes into the cracks in a human femur recovered from the cave to obtain nearly 2 grams (0.07 ounce) of powdered bone. At first, they looked for the signature of ancient nuclear DNA, which could have provided information about the genome of the individual behind the femur — but that information was overwhelmed by the signature of modern-day human contamination.

Then they turned their attention to the mitochondrial DNA, which lies outside the cell's nucleus and is passed down from a mother to her children. That strategy was more successful.

Unusual findingPrevious analysis of bones from the cave had led researchers to assume that the Sima de los Huesos people were closely related to Neanderthals on the basis of their skeletal features. But the mitochondrial DNA was far more similar to that of the Denisovans, an early human population that was thought to have split off from Neanderthals around 640,000 years ago. The first Denisovan specimens were identified in 2010, based on an analysis of 30,000-year-old bones excavated in Siberia.

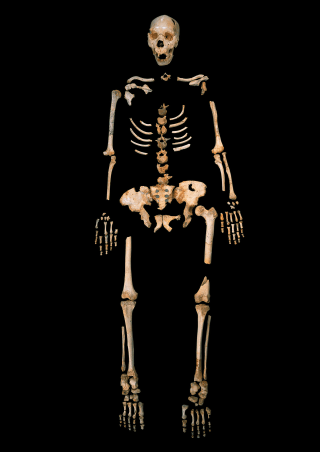

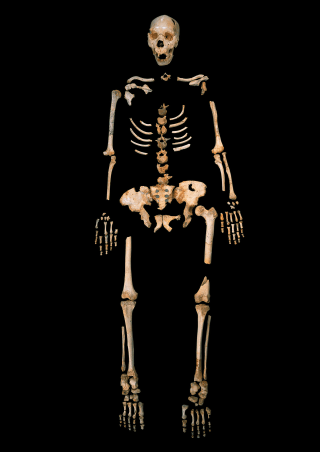

Javier Trueba / Madrid Scientific Films

This skeleton from the Sima de los Huesos cave has been assigned to an early human species known as Homo heidelbergensis. However, researchers say the skeletal structure is similar to that of Neanderthals - so much so that some say the Sima de los Huesos people were actually Neanderthals rather than representatives of Homo heidelbergensis.

The latest DNA analysis sent scientists scrambling for an explanation.

"This unusual finding could be due to at least two different scenarios, both relating to the material inheritance of mtDNA [mitochondrial DNA] and the ease with which it can be lost in a lineage," Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at London's Natural History Museum who was not involved in the Nature study, wrote in an email.

One scenario could be that the DNA was passed down the maternal line from a population that was ancestral to the Sima de los Huesos humans as well as the Denisovans, but that the lineage died out among Neanderthals and modern humans.

The other scenario is that an as-yet-undetermined population interbred with ancestors of the Spanish cave-dwellers as well as the Denisovans. Meyer, Pääbo and their colleagues tentatively favor that scenario. "Based on the fossil record, more than one evolutionary lineage may have existed in Europe during the Middle Pleistocene," they write.

"Either way, this new finding can help us start to disentangle the relationships of the various human groups known from the last 600,000 years," Stringer said. "If more mtDNA can be recovered from the Sima 'population' of fossils, it may demonstrate how these individuals were related to each other, and how varied their population was."

Update for 10:30 p.m. ET Dec. 4: Erik Trinkaus, a paleoanthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis, told NBC News that the DNA findings were interesting from a technical standpoint — but he pointed out that the mitochondrial DNA alone doesn't reveal how the Sima de los Huesos people and their ancestors lived. He suspects that further DNA studies will show that the relationships between populations of early humans were messier and more tangled than the typical diagrams of human origins would suggest. That's appropriate, he said, "because I think the real world is messy."

Alan Boyle, Science Editor NBC News

Dec. 4, 2013 at 1:02 PM ET

Javier Trueba / Madrid Scientific Films

The Sima de los Huesos people lived about 400,000 years ago in Spain.

The oldest human DNA ever recovered is throwing scientists for a loop: The 400,000-year-old genetic material comes from bones that have been linked to Neanderthals in Spain — but its signature is most similar to that of a different ancient human population from Siberia, known as the Denisovans.

The researchers who did the analysis said their findings show an "unexpected link" between two of our extinct cousin species. Follow-up studies could crack the mystery — not only for the early humans who lived in the cave complex known as Sima de los Huesos (Spanish for "Pit of Bones"), but for other mysterious populations in the Pleistocene epoch.

"Ancient DNA sequencing techniques have become sensitive enough to warrant further investigation of DNA survival at sites where Middle Pleistocene hominins are found," the research team, led by Matthias Meyer and Svante Pääbo of Germany's Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, wrote in Thursday's issue of the journal Nature. ("Hominin" is the currently accepted term for humans and our close evolutionary cousins.)

As anthropologists are getting better at extracting DNA from ancient bones, genetic mysteries are cropping up more frequently: Last month, researchers at scientific meetings talked about not-yet-published findings that hinted at interbreeding among Neanderthals, Denisovans and previously unknown populations of early humans.

A new standardThe age of the mitochondrial DNA analyzed for the Nature study sets a new standard: Researchers used statistical analysis of the DNA and other samples to estimate that the material was roughly 400,000 years old. That meshed with the estimated age for similar DNA extracted from bear bones found in the same cave.

More than 6,000 human fossils, representing about 28 individuals, have been recovered from the Sima de los Huesos site, a hard-to-get-to cave chamber that lies about 100 feet (30 meters) below the surface in northern Spain. The fossils are unusually well-preserved, thanks in part to the undisturbed cave's constant cool temperature and high humidity.

Javier Trueba / Madrid Scientific Films

The thigh bone of a 400,000-year-old hominin yielded mitochondrial DNA for analysis.

Researchers drilled a series of tiny holes into the cracks in a human femur recovered from the cave to obtain nearly 2 grams (0.07 ounce) of powdered bone. At first, they looked for the signature of ancient nuclear DNA, which could have provided information about the genome of the individual behind the femur — but that information was overwhelmed by the signature of modern-day human contamination.

Then they turned their attention to the mitochondrial DNA, which lies outside the cell's nucleus and is passed down from a mother to her children. That strategy was more successful.

Unusual findingPrevious analysis of bones from the cave had led researchers to assume that the Sima de los Huesos people were closely related to Neanderthals on the basis of their skeletal features. But the mitochondrial DNA was far more similar to that of the Denisovans, an early human population that was thought to have split off from Neanderthals around 640,000 years ago. The first Denisovan specimens were identified in 2010, based on an analysis of 30,000-year-old bones excavated in Siberia.

Javier Trueba / Madrid Scientific Films

This skeleton from the Sima de los Huesos cave has been assigned to an early human species known as Homo heidelbergensis. However, researchers say the skeletal structure is similar to that of Neanderthals - so much so that some say the Sima de los Huesos people were actually Neanderthals rather than representatives of Homo heidelbergensis.

The latest DNA analysis sent scientists scrambling for an explanation.

"This unusual finding could be due to at least two different scenarios, both relating to the material inheritance of mtDNA [mitochondrial DNA] and the ease with which it can be lost in a lineage," Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at London's Natural History Museum who was not involved in the Nature study, wrote in an email.

One scenario could be that the DNA was passed down the maternal line from a population that was ancestral to the Sima de los Huesos humans as well as the Denisovans, but that the lineage died out among Neanderthals and modern humans.

The other scenario is that an as-yet-undetermined population interbred with ancestors of the Spanish cave-dwellers as well as the Denisovans. Meyer, Pääbo and their colleagues tentatively favor that scenario. "Based on the fossil record, more than one evolutionary lineage may have existed in Europe during the Middle Pleistocene," they write.

"Either way, this new finding can help us start to disentangle the relationships of the various human groups known from the last 600,000 years," Stringer said. "If more mtDNA can be recovered from the Sima 'population' of fossils, it may demonstrate how these individuals were related to each other, and how varied their population was."

Update for 10:30 p.m. ET Dec. 4: Erik Trinkaus, a paleoanthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis, told NBC News that the DNA findings were interesting from a technical standpoint — but he pointed out that the mitochondrial DNA alone doesn't reveal how the Sima de los Huesos people and their ancestors lived. He suspects that further DNA studies will show that the relationships between populations of early humans were messier and more tangled than the typical diagrams of human origins would suggest. That's appropriate, he said, "because I think the real world is messy."