From Earth Changes Media

Breaking News

Tsunami Forecasting: The Next Wave

By Earth Changes Media

Mar 13, 2012 - 2:13:52 PM

A year after the March 2011 devastating Japan tsunami, scientists and emergency managers are still struggling to improve their tsunami detection and warning systems before the ocean strikes again. Japan will soon start to install a 32.4-billion (US$402-million) system of ocean-bottom sensors to provide advanced warnings of tsunamis heading towards the coast. And the United States is considering moving some of its deep-ocean warning buoys off the Pacific Northwest coastline closer to the Cascadia subduction zone, where a mammoth quake is expected, perhaps within the next few decades.

As soon as the shaking died down on 11 March last year, Ken-Ichi Sato stumbled back to his office and pressed the alarm button, triggering sirens throughout the city of Kesennuma in northeastern Japan. As the emergency manager of the coastal community, Sato had to alert the 64,000 people there that a tsunami might be coming.

A minute later, that threat became more real when Sato received word from the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) that the quake was large - magnitude 7.9 - and located off the coast of Miyagi Prefecture, where Kesennuma is located, in the Tohoku region. Residents there should brace for a 6-metre tsunami, warned the agency, and the neighbouring Iwate and Fukushima prefectures should prepare for waves half that height. Sato immediately issued an evacuation warning over the city's loudspeakers.

But when the tsunami hit around half an hour later, it dwarfed the original JMA estimates. The water surging into Kesennuma reached 9 metres high, and the waves battering other coastal sites topped 20 metres, pouring over the sea walls and barriers that buttress much of the Tohoku coastline. Some 15,000 people died as a result of the tsunami - some of whom had reportedly not fled to higher ground because the projected wave heights had made them think they were safe. In Kesennuma alone, 1,031 people died and hundreds are missing.

Sato thinks that the toll might have been lower had he learned the true size of the tsunami earlier. "We could have raised the intensity levels of the alerts," he says. "We could have made sure that people got to a high-enough place."

A year later, scientists and emergency managers are still struggling to improve their tsunami detection and warning systems before the ocean strikes again. Japan will soon start to install a 32.4-billion (US$402-million) system of ocean-bottom sensors to provide advanced warnings of tsunamis heading towards the coast. And the United States is considering moving some of its deep-ocean warning buoys off the Pacific Northwest coastline closer to the Cascadia subduction zone, where a mammoth quake is expected, perhaps within the next few decades.

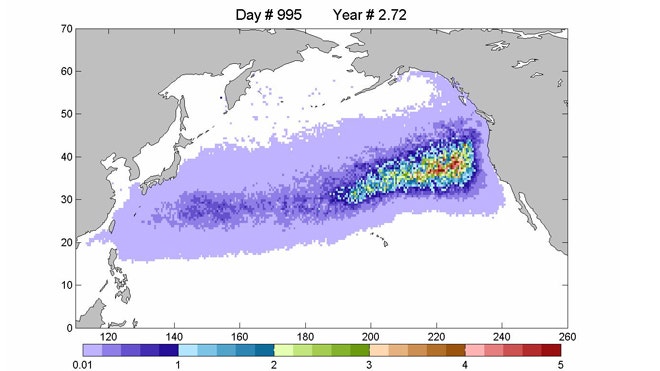

The efforts are an extension of advances made since 2004, when a tsunami caused by an earthquake off the coast of Sumatra killed more than 230,000 people. The disaster raised awareness of tsunamis and prompted nations to pump money into research and equipment. As a result, emergency managers can now effectively forecast how tsunamis will cross ocean basins and hit coastlines thousands of kilometres from a quake's source.

The next, more difficult, goal is to improve warnings for close-in regions, which may only have minutes to react. "Historically, maybe 95% of tsunami deaths are from local or regional tsunamis," says Laura Kong, director of the International Tsunami Information Center in Honolulu, Hawaii. "How do the United States and the global community address that with the resources we have?"

Japan intends to meet that challenge with its new sensor network, which is designed to keep tabs on the eastern coastline (see 'Safety net'). Operated by the National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Prevention (NIED) in Tsukuba, the system will consist of 154 sea-floor observatories, each of which contains a seismometer and a water-pressure gauge that can sense the passage of a tsunami, according to Toshihiko Kanazawa, head of the team developing the network. Fibre-optic cables will connect the units in six long loops that each reach the coast at two widely separated locations. According to the NIED, that design will keep the system online even if tsunamis damage a land station or destroy a cable, as happened last March to some sea-floor sensors stationed off the Tohoku coast. The plan is to finish the new network by the end of March 2015.

A large cabled network is already in place in the Nankai trough area south of Tokyo, where a large earthquake is expected in the coming decades (see Nature 476, 391-392; 2011). The system is "field-proven", says Kanazawa. "Its simplicity is suitable for tsunami warning use."

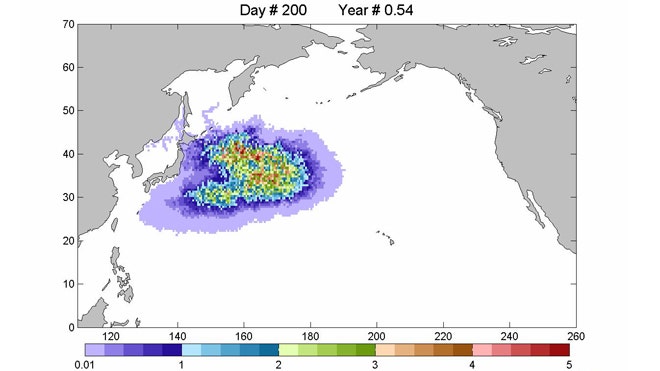

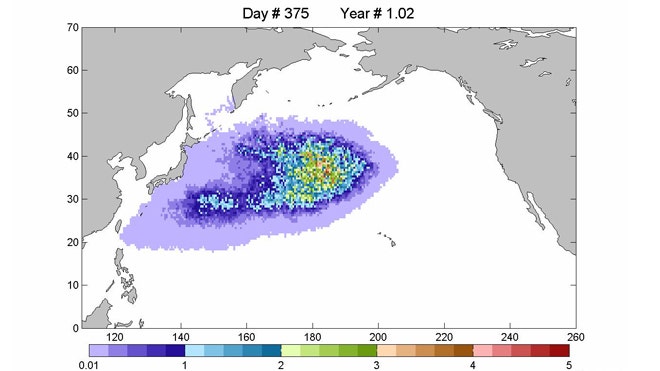

The NIED sensors will sit between the coastline and the earthquake source - the offshore trench where the Pacific plate dives beneath the plate carrying northern Japan. When the Pacific plate jerks forward, the edge of the overlying plate springs up and displaces a huge volume of water, triggering a tsunami. The waves race through the deep water of the open ocean at speeds of roughly 700 kilometres per hour. They alter the sea level by only a metre or two at most as they travel far from the source. But when they hit shallow water, the waves slow down to less than one-twentieth of their former speed and rear up, creating giant surges that sweep ashore. When the NIED network is in place, it will detect the pressure change caused by the tsunami as it travels from the deep ocean over the continental shelf, providing between 5 and 20 minutes of warning for people on the shore.

As a complement to that system, the JMA plans to install three sea-floor sensors on the opposite side of the subduction zone, to catch tsunamis as they speed through the open ocean. Instead of transmitting data through a cable, these sensors will send acoustic signals to nearby buoys that then relay the information up to geostationary satellites. The buoys can be installed faster than the cabled network and will be put in place this year, says Kanazawa.

They will be part of an existing network of buoys known as DART, for Deep-Ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis. The United States has 40 such buoys stationed around the Pacific and Atlantic, and other nations have purchased 14 buoys, which are positioned at sites in the Pacific and Indian oceans, with almost all of the data shared internationally.

The impetus to develop the DART system came in part from an expensive false alarm, recalls Eddie Bernard, who designed the system and retired as head of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory (PMEL) in Seattle, Washington, in 2010. When a magnitude-8.0 quake struck the Aleutian Islands in 1986, Hawaii evacuated its beaches and other low-lying coastal areas at a cost of some $40 million, including lost revenue. But when the tsunami washed ashore, it was only about 15 centimetres high. The civil-defence leader called up Bernard, who was head of a lab doing tsunami research, and said: "Why can't you do better?"

The programme got a boost when a 1992 earthquake off the coast of northern California raised concern that the Cascadian subduction zone might let loose with a giant earthquake and trigger a devastating tsunami. So in 1997, Congress provided funds for a tsunami mitigation programme, and Bernard finished his long-term project to develop deep-ocean tsunami sensors.

He and others originally thought of DART buoys as sentinels for the entire ocean, watching for tsunamis from distant earthquakes - the type that usually threaten Hawaii. The buoys had accordingly been stationed far out to sea, both to catch the largest number of tsunamis and because researchers worried that if the sensors were close to the source of an earthquake, the seismic vibrations would drown out any tsunami signal.

But the Tohoku quake changed that thinking. At a meeting in January at the PMEL, Japanese and US scientists discussed ways to filter out the seismic vibrations from the sensor data, which would mean that the sensors could be deployed much closer to faults, says Vasily Titov, a tsunami modeller at the PMEL. "We can put the sensors in a place 5 minutes away from the sources," he says. Once the front of the tsunami reaches a DART sensor, Titov says, it takes another 5-10 minutes for half of the wave to pass by, thereby revealing the height of the tsunami.

The United States is now hoping to move some of its DART buoys nearer to earthquake sources - along the Cascadia subduction zone and in many other regions, says Titov. Warning centres will then combine the DART data with spatial models of coastlines to predict the severity of the flooding more quickly. "Within half an hour, you can get a very high-quality forecast showing which areas are going to be inundated," he says. And that would help emergency managers to decide which areas should be evacuated, and when to urge people to move to higher ground.

In the regions closest to an earthquake, however, many people would die if they waited for those results. The first waves from a Cascadia tsunami can hit in 15-20 minutes, and the problem is even worse in Japan and the Aleutian Islands, where some regions have only a few minutes of lead time. Emergency managers are therefore developing a tiered approach, in which they issue quick warnings that are updated as measurements come in from the sea-floor sensors.

Ups and downs

The Tohoku earthquake shows how those data can help - and hurt. At an international meeting last month in Sendai, Japan, Osamu Kamigaichi from the JMA described some of the problems that his agency ran into during the disaster. When the quake struck at 2:46 p.m. local time, the agency quickly determined its size and location from records of short-period seismic waves, the first data to become available. The JMA then used pre-computed tsunami simulations for the estimated quake to forecast the height of the waves. The warning with those details went out within 3 minutes.

This method works well for quakes smaller than magnitude 8, but it can't gauge the size of larger shocks. The JMA didn't consider that a problem, however, because the estimated size of the Tohoku event was 7.9, about the size of the largest earthquake expected there. But the quake turned out to have a magnitude of 9.0, more than ten times stronger.

The first hints that something was amiss came at 2:58 p.m., 9 minutes after the first warning, when a cabled pressure sensor picked up an unexpectedly large change in sea level off Iwate prefecture (see 'Warning signs'). But the agency did not have a fully developed method for using data from that sensor to update the tsunami warnings.

Â

Earth Changes TV